Narrative Roadblock or Immersive Aid: A Question of Morality

When I was twelve, Fable captured my imagination like few games had, or have been able to since. Though far from being the first video game to implement a moral choice system, it came at a time when use of the mechanic in RPGs was building momentum (Bioware’s seminal Knights of the Old Republic was released one year earlier), and since then we’ve seen more and more games integrate some sort of player-decision element.

I played through Fable multiple times, and whether I chose to be a silver-bearded mage with glowing hands and the faintest of halos, or a huge, bulking, battle-axe wielding monster, two proud horns jutting from my forehead, each character crafted brought me huge satisfaction. My decisions mattered, or so I thought: protect the orchard; slay Twinblade; have mercy on Whisper.

But as the mechanic has developed, the transparency of a black/white choice system has become all the clearer. Want glowing red eyes and broken blue skin? Then go beat up a child, steal some hairstyles, and eat a crunchy baby chicken or several. Want all your crew to perceive you as a rad, Luke Skywalker-incarnate, Jedi paragon? Then do the obvious and negotiate your way out of fights and help those in need. How much variation is there really?

The amount of times I’ve felt forced into making a certain decision because I’ve already chosen whether to play the game as a ‘good guy’ or a ‘bad guy’ and don’t want to mark my perfect record, is way too many. Nobody plays to mix-up the decisions, or act ‘like they really would’, because nobody wants a boring grey, neutral character. Furthermore, game developers encourage this sort of playing - they place some of the story-telling responsibility on our shoulders, knowing full-well that we’ll choose to try and weave a coherent plot by picking a side and sticking to it. And what do we end up with? Another linear narrative.

I wanted to kill the Rachni Queen in Mass Effect, but refrained from doing so for the paragon points; I had mercy on Death’s Hand in Jade Empire only because it was in line with my chosen ‘way of the open-palm’, and was devastated when several of my party members revolted against the decision. Choice is a facade if we feel pressured or obligated into a decision, and our immersion into a story is hampered when the narrative feels forced or contrived.

So a more complex morality system is called for. Or, at least, one that is less blatant than just good vs. evil. I’m a long-serving Bioware fan, and there’s been a noticeable development away from the stark system used in their Star Wars games: Jade Empire’s ‘open palm’ and ‘closed fist’ definition is meant to represent the difference between discipline and pragmatism, and Mass Effect’s paragon/renegade choices reflect how your character deals with situations rather than the goodness of their heart. A welcome move away from black/white morality, but the two-sided coin problem persists; it’s one way or the other.

I loved how the issue was tackled in Dragon Age: Origins. Bioware cast away the moral alignment bar and focused on the affect your decisions had regarding the relationships with your party, each individual holding their own opinions in the various dilemmas faced. This ensured friction between you and certain party members; you couldn’t please everyone and it was a real pain maintaining loyalty through the character-specific side-quests. This encouraged you to assess every party member’s loyalties and opinions afresh with each decision rather than stick to a set path.

Dragon Age’s story felt like my own. I built relationships with characters that I wanted to, and clashed with those I didn’t. As a result, I felt more freedom to create a story unique to me within the confines of the narrative in which I had immersed myself.

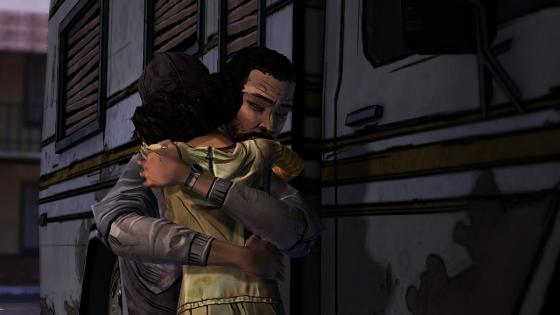

Last year, Telltale’s The Walking Dead took complex decision-making further. No bars, metres or anything to track either morality or relationships, only the occasional note such as ‘Kenny will remember that’ spelled out the affect your choices were having. Game altering decisions were no longer just a thing met at forks in the narrative path, but became a constant feature of conversations; you’d get three or four options, none of them morally right or wrong, each making a subtle adjustment to how a character perceived Lee. Alongside the major decisions, these minor differences ensured the personalisation of your playthrough.

The responsibility feels huge - Lee’s morality is completely under your control, and the consequences of his actions are yours to deal with. It still surprises me when I hear people talk about The Walking Dead’s ending, because the story feels like something that I alone experienced. That kind of immersion is a difficult thing to capture, and was achieved through the complex and numerous moral choices available to the player.

However, with this much freedom come other problems. Developers aren’t willing to write strands of story heading in new directions to accompany every single decision, and it’s not rare in choice-based games to see your actions later neutralised by compulsory plot direction. For instance, saving a character only to see them killed off anyway later on. It’s an obvious compromise that can’t really be blamed, but as the seams start to show, our immersion is hampered nonetheless. Seeing the futility of our actions in the game’s wider plot movement pulls us out of the moment - nobody wants a developer’s perspective when trying to sink into a game.

This isn’t to say that multiple paths and endings are the only way for a moral-choice system to work, however. One of the most immersive narratives from last year was that of Spec Ops: The Line -a game that implemented a pretty bare-bones choice system. Decisions were infrequent and the options were always limited; none but your final choice impacted the ending, and the story moved in a straight line throughout, regardless of the options you chose. In contrast to the attempts of other games that use a choice mechanic, the decisions in Spec Ops granted the player very little freedom over Martin Walker’s fate.

As a result, Walker’s developing morality and how you chose to shape him as a protagonist never had a direct impact on the course of the story. What it did offer, however, was the ability to completely change your perspective and mould your view of Walker. Spec Ops forces you to make some very difficult decisions, and depending on how you choose to approach them, you can end up with a protagonist with whom you either sympathise or completely despise. I never felt so potently about my evil player-made characters as I sometimes did about Walker, a feeling attained by having a protagonist who isn’t completely under your control, and a plot that you are helpless to change. It’s less the destination that matters in Spec Ops: The Line, and more the journey. We’re never responsible for the direction of the plot, but we have a huge hand in the shaping of the protagonist and, therefore, our experience of the story.

I’m not saying that we should have freedom taken away for the sake of immersion (I would be devastated if Bioware began to make their games more linear), as freedom and control over your character’s moralities can be equally compelling. But having a story in which we are responsible for the protagonist’s actions doesn’t just have to be about player-made characters, party interaction, or picking whether to be a good guy/bad guy.

COMMENTS