Death of Utopia

Analysing the response of videogame developers to ‘The Death of Utopia’

The concept of utopia is one of great intrigue, an almost intangible worldview that serves as more paradoxical than it is possible. The greatest curiosity that surrounds it is how simple of an idea it is, and yet historically, an impossible dream that has evaded mankind for as long as we have strived for it, as Margaret Atwood explains:

“Utopia" is sometimes said to mean "no place", from the Greek ou-topos; others derive it from eu, as in "eugenics", in which case it would mean "healthy place" or "good place". Sir Thomas More, in his own 16th-century Utopia, may have been punning: utopia is the good place that doesn't exist.

Looking now at the videogame industry, I will be analysing its response to the death of utopia, using 2k games' Bioshock: Infinite and Bethesda's Fallout 4 as examples. From the psychology of utopian dreams and the philosophy that humanity has evolved into, this article will explore examples of utopian death as well as the way in which developers have used this concept to carry on a timeless message.

We begin at the greatest human disillusionment toward utopian concepts that became abundant both during and after World War II. A universal catastrophe born of a yearning for global perfection that dropped the scales from our eyes. In an essay discerning the philosophy behind utopia, Leszek Kolakowski introduces the disaffection with utopia as seen in the work of 20th-century authors: “The great works of our century are anti-utopias or kakotopias, visions of a world in which all the values the authors identified themselves with have been mercilessly crushed (Zamyatin, Huxley, Orwell).” While seemingly irrelevant to a discussion about videogames, the artistry found within them draws parallels to numerous older sources of literature: various Orwellian philosophies and ideals can be seen in the Fallout franchise, for example, as well as Herbert Marcuse's One Dimensional theory.

In Bioshock: Infinite, instead of the player being placed in a dystopic reality, they are presented with a failing utopia. Beginning in Columbia, a floating, colonial city that boasts picturesque streets and good old fashioned racism, the protagonist is quickly thrown into a chaotic downfall that rampages its way through the city. Along the way, information can be gathered about the development of Columbia, its laws and principals, the Vox Populi rebel uprising and a girl named Elizabeth.

Columbia was designed specifically to parade America's pride and joy, a heavily patriotic city that seemingly represents America on the edge of modernity. With its steampunk aesthetic undercut with colonial brutality, Columbia perfectly embodied the American dream. From the motorised patriots that the player must destroy as they go to the museum depicting the battle at Wounded Knee that paints Native Americans as bloodthirsty savages, Bioshock: Infinite puts across conflicting imagery designed to question patriotic morality.

Many of the laws that were enacted in its heyday were reminiscent of both Apartheid and pre-civil rights America; implementing segregation that targeted black people and those of a low socio-economic standing. As the game progresses, the player is plunged into deeper realms of discord. The story follows a post-modernist stream that one could argue emanates the multidimensional conflicts found in dystopian scenarios, at the forefront of these conflicts we see a divide between Columbia's founder, Zachary Comstock and the radical uprising known as the Vox Populi: a militant group made up of the oppressed citizens that rebel against the status quo, terrorising the city.

The last pillar of a crumbling utopia can be seen in the character of Elizabeth; Comstock's desperation for an heir resulted in 'The Lamb of Columbia', aka Elizabeth being imprisoned and isolated for the majority of her life. Her character seems to represent a catalyst for change, with the combination of her supernatural ability to harness “the tear” and her innocent, pure persona. She stands as a blank slate, a symbol of objectivity, and someone equipped with the tools to reinvent their culture. Whatever happens to her may seal Columbia's future.

From beginning to end your character bears witness to the collapse of the white-washed empire, which in itself is a variation of kakotopia, but when deconstructing the layers that made up Columbia's dictatorship, one sees a puritan nightmare comparable to Bertolt Brecht's Fear and Misery in the Third Reich. In this, the developers have responded to colonialism in both modern and historical formats, creating a criticism of American civilisation and how it developed. Essentially, 2K Games have opened up a dialogue that questions the virulent nature of humanity, and our paradoxical search for perfection within a community.

Fallout 4, along with its predecessors, fits itself into the cliché themes of dystopia by dominating post-apocalyptic fiction. While there is a clear difference between apocalyptic themes and the death of utopia, in many ways the two go hand in hand. With Bethesda's understanding of societal constructs and patterns, they are able to appeal to the general association of apocalypse with utopian death. In their most recent title, they continue the saga of introducing players to a world torn apart by a human striving for power. More specifically, atomic power, which is utilised in this old-world America setting to keep the lights on, and eventually reduces the nation to rubble.

The 1950s visage of Fallout, that acts as a weird candy coating for the radioactive wasteland, represents a willful ignorance that denied any responsibility for the destruction it brought about. Here we see Herbert Marcuse's One-Dimensional Theory; During the 1950s era, America entered a cultural state of denial in the form of consumerism and false happiness, burying their heads in the sand to issues such as post-war racism. With its eerily upbeat soundtrack as your adventurous overture, to accompany the time spent blowing the heads off of irradiated bears, the setting is given a ghoulish contrast. The divide between white picket fence suburbia and the burnt out war-zones within the wasteland is there to point out the ugly sentiment of post-war America.

The game's tagline “War never changes” not only sums up the game in its entirety but sends out a message that solemnly condemns violent, human nature. Fallout 4 builds from previous titles by expanding upon points such as hegemony, scientific advancement and communism vs imperial capitalism. It also progresses the story of mankind's relationship with technology, exemplified with both the Brotherhood of Steel and The Institute, the latter making its debut appearance in Fallout 4.

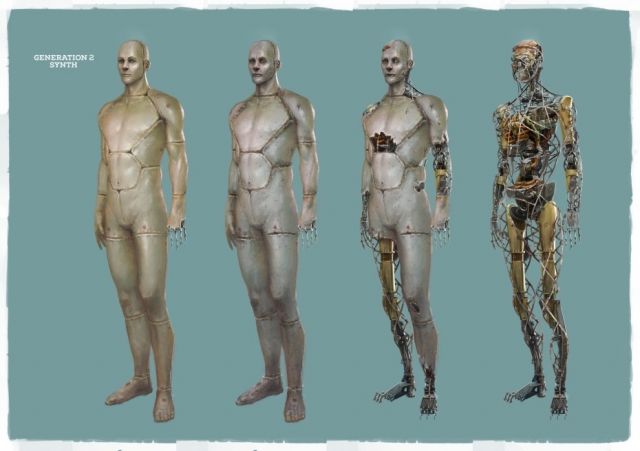

Hegemony and scientific advancement can be seen in the ranks of The Institute; the faction has amassed an army of synthetic people and uses their threat to hold power over the Commonwealth. The institute's primary vocation is science and technology, with which they routinely experiment and have grown notorious for it. This segment of civilisation within the Fallout canon is a reference to the age-old dynamic of man playing god, it relies upon the belief of knowledge being the ultimate source of power. With both their physical army and their advancement, they gather influence, which in turn creates dominion.

To those within the faction, The Institute displays a level of respect; employees and their families are given the option of a comfortable, happy life. Yet the effects their research has on those outside paints a different picture. From your character to the people of Diamond City, looking specifically at Conrad Kellogg's involvement, this faction holds a sinister reputation, and some could say that it is the scientific and militant strive for power that brought about armageddon.

Moving on to militant power, in Fallout 4 we are reunited with the Brotherhood of Steel, who follow backward objectives to deprive the world of technological power (specifically weapons), with this we see an opposite of The Institute's morality (well, almost). While they believe most forms of technology to be too dangerous for general use, they use technology and technological weaponry to achieve their goals. The Brotherhood of Steel display paranoia on par with Joseph McCarthy; isolating power for themselves out of fear for its potential, yet using that power out of fear for the potential of others. It could be argued that such a fear of total annihilation is ill placed in a world with little left to destroy. Looking at these two factions as examples, the underlying message behind the game can be delineated.

From the Iraq War to the airstrikes in Syria, the developers seem to be pointing toward our feasible future; Fallout 4 specifically references World War II in its opening cinematic, and while the game follows an alternative timeline, it's suggestive of the timeline we exist in. Using parallels and purposeful imagery that tie the situation back to the most devastating event the world has seen. It would seem that Bethesda's response to the death of utopia is a carefully constructed prediction of society's inescapable demise through its search for power, combined with the possible belief of us rising to repeat the same mistakes, no matter what we've experienced.

Dystopia within fiction is clearly a popular and entertaining subject to draw upon. With the unlimited potential for concepts and its sublime qualities, it has become increasingly enticing to both videogame audiences and developers. However, when we look at games as artistic pieces that serve a greater purpose than escapism, we have to look at their themes in the same way one might analyse films or literature. Based on the information gathered, it’s clear that the developers have put effort into reinvigorating the 20th-century movement; perhaps it’s little more than a subject of interest to them, their own personal expression, or perhaps it’s their way of sending out a message. Considering the tempestuous history of human civilisation in conjunction with these sorts of artistic concepts, it’s hard to not envision titles such as these as criticisms or even warnings. The critical and precautionary tales of Huxley, Orwell, Palahniuk and Marcuse have left their mark on the minds of 21st-century creators, and the response of these creators communicates this in an arguably louder voice.

COMMENTS